St Paul's Missionary College

Its life and historySt Paul’s Missionary College

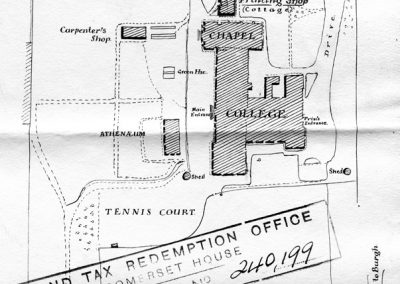

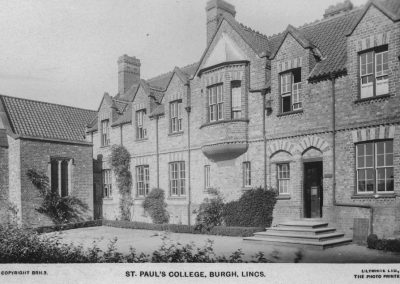

In 1868 Revd W. S. Thomason opened the Burgh Middle School in Burgh-le-Marsh. In 1877, the school closed. Revd J. H. Jowett acquired the school buildings for the purpose of founding St Paul’s Mission House, a missionary training college which acted as a feeder to St. Augustine’s, Canterbury. It was dedicated by the Bishop of Lincoln, Dr Christopher Wordsworth, on the feast of St Paul in 1878.

After a few years it was recognised as a Theological college with affiliations to Durham University. St Paul’s college was open to all with a calling to serve God. Its hood was an Oxford simple in black with a white silk-lined cowl.

On 17 December 1894 the Bishop of Lincoln, Edward King, consecrated a fine college chapel designed by the celebrated architect John Ninian Comper (1864–1960). This chapel would be central to life at the college, even during the First World War (1914–1918), when parts of the college complex were used as an Officers’ Mess for the Cumberland and Westmoreland Yeomanry. Students who were eligible to serve joined up and two were sadly killed in action. For those students who were exempted from national service, life went on as normally as it could, with much more limited space due to the military’s occupation of the complex. Remaining students were often joined by disqualified men from other colleges when their institutions closed.

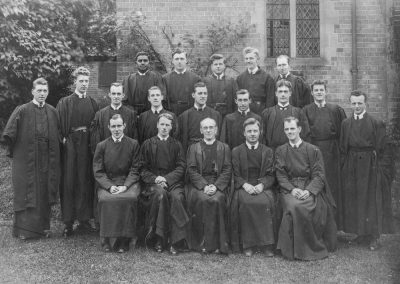

Following the end of the war, the number of students at the college gradually increased and they took a full and active part in local life, teaching at the Sunday School and taking services in St Peter and St Paul’s parish church.

In 1936, the Committee of the Church Assembly changed its policy for the training of clergy, which made St Paul’s College redundant. Upon its closure, the Bishop of Lincoln wrote in a letter;

‘…We thank God…for the devotion all the old Burgh men all over the world, and for what they have been aa well as for what they have done. I share with you all the inevitable sorrow that the closing of the College brings…’

The former college buildings were occupied by the military during the Second World War (1939–1945). After the war, it became a girls’ boarding school, and from 1957 a Preparatory school for boys, which closed in 1965. The building was demolished in 1969.

The altar, inscription boards and a banner from the college are now in St Peter and St Paul’s. The stalls were transported to Sheffield Cathedral. A stone tablet on the edge of St. Paul’s bungalow estate stands as a memorial to the college. And a three-light stained glass window by Comper depicting the Conversion of St Paul (1929) was transferred from St Paul’s College Chapel to the parish church of St Mary, Manby.

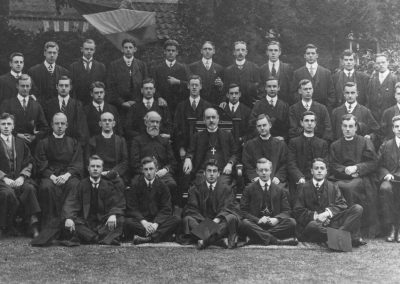

Life at St Paul’s College

St Paul’s College promoted a ‘simple, strenuous, regular and happy life: devotion and discipline, study and exercise, healthy recreation and godly mirth, a plain but amply sufficient diet, and an invigorating sense of fellowship with heroic missionary souls in nearly every part of the world’. It was as inclusive as a clergy college could be and charged £90 per annum in fees.

Many students took the general ordination exam whilst others read for the Licentiate of Theology before undertaking a BA degree at Durham University. Some were ordained to a curacy in England before going overseas, while others followed their calling to spread the Gospel across the world immediately after completing their studies at St Paul’s.

Men from the college would go to, among other places;

• Zululand

• Rand

• North China

• New Guinea

• Melanesia

• British Columbia

• Canada

• New Foundland

• British Guiana

• Nyesa

• Bombay

• Trichinopoly

• Melbourne

• Queensland

• Transvaal

• Kaffraria

• Waiapu

• Johannesburg

• Antigua

• Zanzibar

• Qu’Appelle

• Lebombo

• Alaska

• Shantung

• Tasmania

• Barbados

• St Kitt’s

A typical day at St Paul’s

- 6.15 am: the calling bell begins the day

- 7.00 am: Chapel for Mattins, Holy Communion and Meditation (7.30 am on Sundays for sung Eucharist)

- Breakfast

- After breakfast during the summer months: rolling the cricket pitch

- 9.00 am – midday: lectures

- Midday: Sext, followed by manual work, including printing, carpentry and gardening or orderly duty in the chapel or library. Following manual work: cricket or football

- 5.00 pm: Evensong, with plainsong canticles, and hymns from the English Hymnal

- Evening: tennis, croquet, ping-pong

- Supper

- Following supper: lectures and debates

- 9:15 pm: Compline (night prayer)

- Retire to bed

Sundays are usually largely given over to teaching in Sunday School or serving in mission rooms. Saints days are free for rest, rambling and visiting friends.

St Paul’s Principals

Thomas Skelton (Principal, 1878–1883)

Thomas Skelton was the first Principal of St Paul’s Mission House, prior to its becoming a college. He took up the post having previously served his calling in Delhi and Calcutta.

William Arthur Brameld (Principal, 1883–1890)

Brameld, St Paul’s second Principal, enlarged the St Paul’s complex. An addition of particular note was the Wordsworth Library, financed by a bequest from the Bishop of Lincoln, Christopher Wordsworth. The library was a place for quiet reading and writing which was always available to students.

Canon Oldfield (Principal, 1890–1896)

Canon Oldfield was the third Principal of St Paul’s. It was under his watch that the transformation from Mission House to Theological college took place.

Canon T. H. Dobson (Principal, 1896–1912)

Canon Dobson was the fourth principal of St Paul’s. He was a man who expounded the benefits of diligence, firmness and good character. He instilled in his students the notion that the way to success was through prayer, meditation and getting to know both God and self.

Canon Foster (Principal, 1912–1920)

in 1912, Canon Foster retuned to Burgh le Marsh after eighteen years and spells in Capetown, Natal and Matabeleland. Upon his return he became principal of St Paul’s and introduced daily Holy Communion and Eucharistic vestments. He spent his own money in support of students and provided a common room for them. The First World War was a difficult time for Canon Foster, who was deeply opposed to conflict. He acted as an unofficial chaplain to the soldiers stationed at Burgh le Marsh and took on the duties of the parish priest, who had left the town to serve as military chaplain. Canon Foster left his position as principal in 1920 following many years of what was described as over work, handing over responsibility to Canon W. E. Boulter.

Canon W. E. Boulter (Principal, 1920–1929)

Canon Boulter was the vicar of the parish church of St Mary le Wigford, Lincoln prior to becoming Vice Principal of St Paul’s. He became Principal in 1920.

Revd Cecil Osmund Tabberer (Principal, 1929–1936)

Tabberer was St Paul’s final Principal. He joined the college having served in Ardwick in Manchester and South Rhodesia.

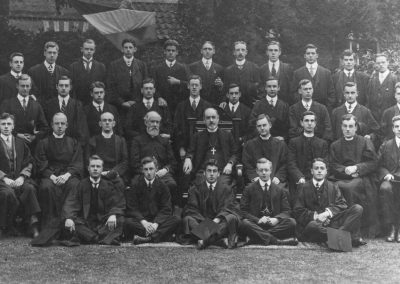

The Men of St Paul’s College

St Paul’s was a missionary college which specialised in training men who felt a calling to spread the Gospel across the world. Many of these men lived remarkable lives. Here are just a few of them and their stories.

Walter Canner and the Hill Murray Institute for the Blind

Walter Canner (1880–1947), from Lincoln, was a joiner by trade, who in the late 1800s took a keen interest in steam locomotion. This led to a job as a shunting engine driver in his local area. Walter’s attitude and application prompted his supervisor to comment that he would be well-suited to missionary work. Walter agreed and attended St Paul’s Missionary College, Burgh-le-Marsh, for three years and three months between 1902 and 1906.

He was ordained by Bishop Edward King (1829–1910) and dispatched to China in 1907, where he was ordained deacon in north china in February 1907 by Bishop Charles Perry Scott (1847–1927) and then in April 1909 ordained, again by Scott, as priest in the Peking Missionary Church, eventually becoming Principal of the Anglo Chinese Secondary School at Yung Ching.

During and immediately after the First World War, Walter went to France, where he worked as Army Transport Arranger for the Chinese Labour Corps, also acting as a translator and welfare officer, ultimately reaching the rank of Major. He then returned to Lincoln.

In 1921, Walter travelled back to China to establish a school for blind boys in Peking, which was to replace the Hill Murray Mission to the Blind and Illiterate Sighted in North China. A seventeen-acre disused burial site at Palichuang, a village a few miles west of the P’ing Tzu Men gate of Peking was acquired as the site of the new school. Around the site Walter constructed a mud wall, and on the south side of a central, man-made mound he built a one-storey dwelling for him, Ethel, his wife, and their son, John. (In 1923, John would be joined by a sister, Mary. Conditions were fairly harsh and the family relied upon paraffin lamps and candles for light and small stoves for heat during the winter. During the summer, it was extremely hot.

The Canners were joined by a local farmer who had fallen on hard times. He lived in a modest cottage on site and was allocated some land for a kitchen garden. This garden issued peanuts, sweet potatoes, sweetcorn and cabbages, feeding the compound and supplying local shops and traders. Water was drawn from a well, the winch of which was powered by a mule.

Walter found himself the first Superintendent of the newly-established Hill Murray Institute for the Blind, which was housed in a U-shaped structure in the compound. Here the boys would learn how to read Braille before being tutored in mathematics, general knowledge and various trades. They would have the opportunity to become proficient in book binding, carpentry, shoe-making and weaving. The weaving workshop had five looms, which were constructed in the carpentry workshop. Walter would teach his pupils how to operate the looms and weave canvas for kit bags and make towels, which were sold through a shop in Peking. They also built cane furniture, chairs, tables and baskets, all of which sold very well. This income was very important as it helped to meet the running costs of the school.

Demand for places grew quickly and additional buildings, designed by Walter himself for the education of blind girls, were erected in 1923. The girls learnt knitting and sewing, mostly learning to mend and make clothes. They were supervised by Ethel and readily sold their wares for significant sums, which, like the products the boys made, helped to pay for the school’s running costs. A gymnasium was added to the school complex in 1924.

Every Christmas the whole school would gather as an extended family in Walter’s home. They would sing carols and receive gifts of peanuts and fruit from their beneficent Superintendent. In 1925, a hall was built, which was used as a church, an amateur theatre and a place for general assembly. The annual Christmas festivities were also transferred there.

During an extended visit to Lincoln in 1926, Walter suffered a stroke, which delayed the family’s return to China by 18 months. Once back in China, Walter set about expanding the Hill Murray Institute, taking on more pupils. After the school had been operational for seven years, it was providing over forty boys and girls with an education.

In 1938, Walter and Ethel returned to Lincoln due to Walter’s continued ill health. He left behind a thriving school which boasted 61 pupils in total, all of whom had either been baptised or were receiving church instruction. Fittingly, Walter was succeeded as Superintendent by Samuel Hill Murray, the son of William Hill Murray, founder of the original Hill Murray Mission.

Right Revd Gordon Tindall, Bishop of Grahamstown (1911–1969)

Gordon Tindall (1911–1969) was born in Burgh-le-Marsh in 1911. He was educated at Alford Grammar School before attending St Paul’s Mission House. Following his missionary training he enrolled at Halfield College, Durham, where he graduated with a BA. He was ordained deacon in 1936 and served as assistant curate at Swinton. In 1937 his was ordained priest and travelled to serve the priesthood in Bechuanaland. He became Rector of Vryburg in the Northern Cape Province, Director of the South Bechuanaland Mission from 1942 before moving to Kimberley-Kuruman. He served as the Rector of St Saviour’s in East London from 1950 and for the next ten years during which time he was also Canon and Chancellor of Grahamstown Cathedral from 1950–1956; Archdeacon of King William’s Town from 1957–1963; Archdeacon of Queenstown from 1960–1962; and Director of Religious Education in Grahamstown until he was elevated to the See of Grahamstown in 1964.

Gordon Tindall was reputedly a man of wise counsel, a dynamic preacher and efficient administrator. A man of great strength of character, intellect and feeling, Tindall also had a wide theological knowledge. He had little time for pomp, preferring a manner of informal dignity in his pastoral and official duties.

Whilst he was a missionary in Vryburg District in South Africa at the beginning of his work overseas, George Tindall typed letters to his family. His words offer great insight into his life at the mission station in the 1930s.

You can read excerpts of some of his letters here